The Siren

The siren was the first artificial sound source with variable known frequency, and therefore helped kick-start the emerging science of acoustics in the early 19th century.

Invention

The siren was invented by the French engineer and physicist Charles Gagniard de la Tour (1777-1859) in 1819. De la Tour was a prolific inventor who was made a baron in 1819 by Louis XVIII for his contribution to science. The siren is so-called due to its ability to produce sound underwater (the Sirens of Greek mythology were sweet singing but deadly female sea creatures who lured sailors to their deaths). The Whipple Museum has five sirens in its collection, all by late 19th century and early 20th century makers such as Max Kohl, and Philip Harris.

Learn how people from across the world have navigated the oceans with help from the Whipple Museum. Use a compass to explore the Museum and play a Pacific-themed trading game. Then make your own bean map to take home.

Free, drop in. All ages.

Location: Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

Function and use

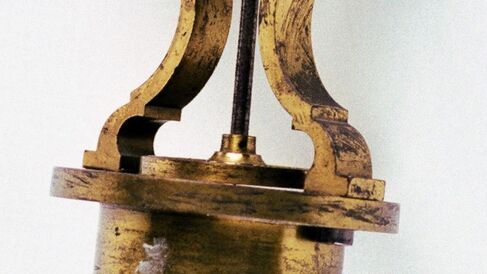

In its most simple form the siren consists of two metal disks, each perforated with equally spaced concentric holes. One disk forms the top of the "wind chest" while the other rotates close to the first. Air is forced through the system, which causes the upper disk to rotate, owing to the slanted bore of the holes. As the disk rotates the flow of air is periodically cut off and reinstated resulting in a regular emission of puffs of air. The ensuing fluctuations in air pressure set up simple sound waves of a specific frequency depending on the speed of rotation of the upper disk. De la Tour arranged for the upper disk to drive a mechanism that can count how many revolutions per second were produced. Knowing how many holes there are in the disks, and thus how many puffs of air per rotation, one can immediately calculate the exact frequency of the sound produced.

The use of the siren in experiments rapidly became widespread. Prior to its invention, scientist had no reliable way to measure or create tones of specific frequency so for acousticians the siren was a great step forward. De La Tour's original design was rapidly improved upon and developed for new and ingenious uses by the great German scientist Herman von Helmholtz (1821-1894) as well as the famed Parisian acoustic instrument maker Rudolph Koenig (1832-1901).

Other uses

Originally the siren was developed for experiments in acoustics but it has long been used also as a form of signaling - for example, to mark the start and finish of working days in factories and building sites. Nowadays the siren (albeit in electronic versions) is used for danger warnings, but it has also been used in classical music, for instance in Edgar Varese's (1883-1965) scientifically inspired composition Ionization (1930).

Torben Rees

Torben Rees, 'The siren: a source of musical sound for experiments', Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge, 2009