Specialist Slide Rules

With the rise of the slide rule as an essential aid to calculation, a number of inventors began to create rules for specialist applications. With no international standards for their manufacture until the late 19th century, slide rules could be highly idiosyncratic. Rules made for specific purposes could have the support of professional groups, and instrument makers vied for their support by catering to specific needs.

John Benjamin Dancer, a Manchester-based instrument maker and inventor, is now best known as the pioneer of microphotography (the production of photographs viewable only through a microscope). He developed the process during the 1840s, and lived to see it become extremely popular, though its first serious use only occurred during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71.

Charles Elcock (1834-1910) was a naturalist, museum curator, and professional microscope slide maker who spent his working life in Belfast. In September 2015 the Whipple Museum acquired his remarkable personal archive of slides and mounting materials (above). Studied together, these objects, books, and tools provide a rare insight into the often overlooked world of nineteenth century microscope slide manufacture.

These twelve wooden geological teaching models, made in 1841 by the 19th-century engineer and surveyor Thomas Sopwith, were designed to teach geology - the study of the Earth. The different types of wood represent different geological formations, highlighting the orientation of mineral veins and coal seams under the ground. The models are based on measurements of mining districts from the North of England.

These Geometric Models by George Adams were a teaching aid for people studying mathematics in the mid-18th century. Models had to compete with other 2-dimensional aids, such as diagrams in books, and did not remain popular for long.

Chemistry

In chemical reactions, given compounds always combine in the same weight ratios. Tools for calculating proportions between various chemical reactants have existed since at least the work of alchemists in the Early Modern period.

As chemistry later emerged as a professional discipline, special chemical slide rules were developed to aid practical work. By the early nineteenth century the term 'chemical equivalents' was used to defined the proportions in which the common chemical substances (either elements or compounds) combined.

In 1814 the Englishman William Hyde Wollaston proposed using a slide rule from which known chemical equivalents could be read. On this chemical slide rule, distances are proportional to the logarithms of the combining quantities. This makes it straightforward to compute what weights of different chemical substances combine to produce the weight of a given product (or conversely how much of each material results from decomposition). Wollaston's 1814 slide rule used oxygen = 10 as its base value, the figure chosen as a matter of convenience.

Wollaston was yet to be convinced by John Dalton's new atomic theory, calling it "purely theoretical" and, therefore, of no use to the "formation of a table adapted to most practical purposes". Not desirous of "warping my numbers according to an atomic theory", Wollaston thus made oxygen the decimal unit of his scale because oxygen was the most common reactant in numerous important chemical reactions and the number ten was a simple figure to manipulate in calculations.

The Whipple Museum's example (image 1) was made by Martin Ehrmann, Professor of Chemistry at the Universities of Vienna and Olomouc (in Moravia). It too used oxygen = 10 as its base unit, the rule listing 175 entries for elements and compounds in total (compared to Wollaston's original 94).

Brewing

Brewing was important for the development of standardisation in industry as the process had to be monitored carefully and the final proof reported for taxation and the fixing of price. As is still done today, a hydrometer (Image 2) was used to measure the changing 'gravity' of the 'wort', which would start off high due to the presence of fermentable sugars and drop as fermentation continued.

A brewer's slide rule was used to convert these gravity measurements to others measurements, for example degrees Plato or proof, which specified the percentage of alcohol by volume. These scales were not linearly related, and the slide rule made it easier for the busy brewer to monitor progress. Improper calibration at any point could lead to customers getting more (or less) than they bargained for out of a pint!

Finance

The rise of modern commerce relied upon tables that showed changing commodity prices and compound currency exchanges. Any good capitalist would have his ready reckoner on hand when transacting a deal.

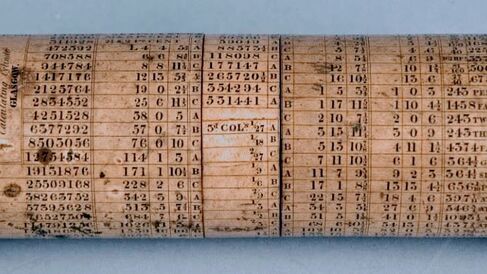

Slide rules were developed to perform financial calculations, such as working out interest, more handily. Rather than flipping through a book, a Victorian banker could align desired conversions using McFarlane's Calculating Cylinder (Image 3), a cylindrical rule. While not a logarithmic slide rule, it made use of rotating scales like in Oughtred'sCircles of Proportion, and inspired the design of further cylindrical rules, including ones that could fit into a shirt pocket.

Military

Galileo's sector had been developed for use as an artillery instrument. With this in mind, it only makes sense that many slide rules were engineered for the purpose of calculating firing ranges.

However, slide rules could also serve other purposes on the battlefield. This example (Image 4) was produced by Lawrence Engineering Service, an American company that mass-produced millions of slide rules in the mid-20th century. It was commissioned by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Radiation Laboratory, and was used for calculating radar antenna beam patterns. This slide rule was considered so strategically important that it's use was classified until after World War II.

Mikey McGovern

Mikey McGovern, 'Specialist slide rules', Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge.