The Stolen Quadrant

On the 2nd of May, 1769, the quadrant belonging to Lieutenant James Cook was stolen from his ship’s encampment on the island of Tahiti.

Cook’s men had journeyed to the South Pacific for two reasons: to observe the transit of the planet Venus across the sun, and to explore and claim territory on behalf of the British Crown.

Astronomy in the British Empire was not just about star-watching from observatories and ships. In the colonies, astronomy was also an essential part of the ‘survey sciences’—a diverse range of geographical practices deployed to chart territory in the service of imperial settlement and administration.

This took astronomers out into the field as part of projects like the ‘Great Trigonometrical Survey of India’, a vast scientific and military undertaking to measure and map the entire Indian subcontinent.

After months of preparation, eclipse observers only had a few short minutes to perform the many tasks expected of them. Popular accounts of these dramatic events celebrated British mastery of astronomy, imperial greatness, and the observers’ superiority over native populations. But records and reports from eclipse field sites reveal a more complicated picture of colonial fieldwork.

In the second half of the 19th Century, astronomers became infatuated with the sun. Eclipse expeditions, in particular, became key events in the astronomical calendar. Their complex planning and execution reveal how the tools of empire were as important as the new tools of astrophysics in these projects.

Astronomical observations performed several key functions within colonial survey sciences. Portable instruments could be used to find local time, orient field stations to true north, and fix longitude and latitude by tracking celestial motions.

In India in particular, this highly accurate mapping work then anchored local revenue surveys that formed the basis for colonial tax regimes.

The two crates shown in Image 1 are time capsules from an eclipse expedition. Shipped out from the University of Cambridge’s Solar Physics Observatory sometime in the mid-20th Century, they were returned after use, sent to storage, and then forgotten.

Half a century later they were rediscovered and reopened for the first time since their final use in the field.

Between 1876 and 1902 somewhere between 12 and 29 million people starved to death in India. As a succession of devastating famines swept through the country, British colonial rule came under attack for its role in the management of food resources and grain exports.

In response, some British experts offered astronomy as the solution. They argued that by using Indian observatories to scrutinise sun-spot patterns, monsoon failures could be understood as natural, predictable consequences of solar variation.

“A matter of astonishment”

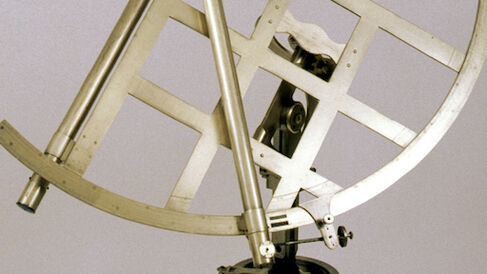

Cook and his men had arrived at Matavai Bay, Tahiti, in mid-April with the intention of observing the transit of Venus from there on the 3rd of June. After building a fortified encampment to “protect the observers and the instruments from the natives,” Cook was surprised to discover his valuable quadrant (Image 1) had been taken by a local inhabitant.

His journal records the scene from his perspective:

“This morning [May 2nd], about 9 o’clock, when Mr. Green and I went to set up the Quadrant, it was not to be found. It had never been taken out of the Packing Case … since it came from Mr. Bird, the Maker; and the whole was pretty heavy, so that it was a matter of Astonishment to us all how it could be taken away, as a Centinal stood the whole night within 5 Yards of the door of the Tent where it was put …

"However, it was not long before we got information that one of the Natives had taken it away and carried it to the Eastward.

"Immediately a resolution was taken to detain all the large Canoes that were in the Bay, and to seize upon Tootaha and some others of the principal people, and keep them in Custody until the Quadrant was produced.”(1)

After some negotiation the instrument was eventually recovered, damaged but repairable, and the transit successfully observed. But upon its return to Britain the voyage’s results were criticised by the Astronomer Royal, Neville Maskelyne.

Cook fumed in private that Maskelyne “was not unacquainted with the quadrant having been in the Hands of the Natives, pulled to pieces and many of the parts broke, which we had to mend in the best possible manner we could.”(2)

A shell trumpet

In encounters between Cook’s men and Pacific Islanders the exchange of goods was a crucial, if sometime fraught, form of social interaction.

After the return of Cook’s quadrant, “a hog and a dog, some cocoa-nuts, and bread-fruit” were formally gifted to the sailors by “The king, whose name was Tarrao”. In return Cook’s men offered “an adze, a shirt, and some beads, which his majesty received with apparent satisfaction.”(3)

Cook and his men collected a huge amount of Polynesian material on their journey through the South Pacific. Joseph Banks, the voyage’s young naturalist, was particularly acquisitive and many of the specimens and artefacts that he brought back to England have ended up in major UK collections.

Image 2 shows a shell trumpet collected on Tahiti during the voyage. Whilst we have numerous reports by Cook and his men, objects like this are amongst the only surviving evidence from the islanders’ side of these encounters.

“In the name of the King”

Upon leaving Tahiti, Cook opened a second set of orders that had been handed to him, sealed, before his departure. These instructed him to begin a search for the postulated southern continent of Terra Australis, and if found to chart its coast, observe and collect its flora and fauna, and attempt to make contact with any indigenous populations that might be encountered.

Significantly, Cook was also instructed to “with the Consent of the Natives … take Possession of Convenient Situations in the Country in the Name of the King of Great Britain: Or: if you find the Country uninhabited take Possession for his Majesty by setting up Proper Marks and Inscriptions, as first discoverers and possessors.”(4)

Today it is this second mission that is better remembered, as Cook would go on to lay claim to both New Zealand and New South Wales in the name of King George III.

References

1.James Cook’s Journal of Remarkable Occurrences aboard His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour, 1768-1771, daily entry for 2 May 1769. National Library of Australia (MS 1).

2.Quoted in: Simon Schaffer, ‘Easily Cracked: Scientific Instruments in States of Disrepair’, Isis, vol. 102.4 (2011), 706–17, on p.709.

3.Quoted in: The Voyages of Captain James Cook Round the World (London: Ann Lemoine and J. Roe, [1807]), on p.32.

4.‘Secret Instructions to Captain Cook, 30 June 1768’ (PDF). National Archives of Australia.

Joshua Nall

Joshua Nall, ‘The Stolen Quadrant’, Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge, 2020.