Tables

In an age of Excel spreadsheets it is all too easy to underestimate the table as an innovation with its own unique history. Though not always understood as 'instruments', tables of numerical values were, and still remain, fundamental resources for calculation. In fact, rulers and scales are, in essence, convenient representations of tabular information. The contents of tables include solutions of mathematical functions, astronomical coordinates and tax brackets.

The important role of instrument makers in the history of science is increasingly being acknowledged. Their practical knowledge is no longer seen as 'inferior' to theoretical knowledge, and in many cases the false distinctions between scientist and artisan have been removed. But instrument makers in the 18th-century had varying degrees of knowledge of natural philosophy. Some were involved in the work of scientific societies, some promoted natural knowledge, and some altered their instruments to cope with the demands of their clients. Individual makers sometimes combined several of these activities in their work.

This 18th-century advertisement for a microscope show gives an unusual insight into the history of science. During the 18th century, opinions on the worth of the microscope differed greatly: some maintained that it could demonstrate more of God's creation, others that it was no more than a frivolous diversion.

A popular instrument?

"Why had not Man a MICROSCOPIC Eye? For this plain Reason, Man is not a Fly."

These two lines from Alexander Pope'sEssay on Man are quoted on a loose sheet (Image 1), printed circa 1760, advertising the following:

"To the LOVERS of Natural Curiosity, or Rational Amusement. To be SEEN at Mr. Johnston's Wig Ware-room. A VERY GOOD DOUBLE REFLECTING MICROSCOPE.

Demonstrating the microscope, with his "good Collection of Objects, Insects, and Animalcula", was John Cuff (1708-1772). Cuff's double reflecting microscope, made to the design and specifications of Henry Baker (1698-1774), became extremely popular and effectively replaced the more cumbersome 'Culpeper' design.

Ancient to Early Modern tables

The invention of tabular record keeping can be traced back to third-millennium BCE Mesopotamia, where tablets using columns and rows were used to account for the transfer of various goods and livestock. The classic tables of antiquity could be found in the astronomer Ptolemy's Almagest, which he republished and distributed under the name Handy Tables. Tables of mathematical and empirical values were helpful for organizing observations and calculations, and their clear-cut presentation made them also ideal devices for sharing knowledge.

In early modern Europe, mathematical tables became important resources for simplifying otherwise laborious calculations. John Napier is renowned for his discovery of the method of logarithms, which he published as a treatise in 1614 (Image 1).

Logarithms allowed large values to be expressed as a standard base raised to a power, making them easier to write down and then look up. Furthermore, they reduced multiplication and division to simpler addition and subtraction. This made the possession of accurate logarithm tables essential.

Entering the age of industry

Henry Briggs (1561-1630), the first professor of geometry at Gresham College in London, was enamoured with Napier's system and worked to recalculate and distribute his logarithm tables widely. This was the beginning of the long tradition of checking calculations and republishing tables, often as pocket-sized 'ready reckoners', for commercial transactions - a practice that became more common during industrialisation.

However, accuracy was always a problem with tables calculated by human 'computers', as error could be introduced during calculation, copying, or typesetting. It was for this reason that this era also saw the first attempts to design and build machines capable of computing and printing tables mechanically.

Read more: early mechanical calculators

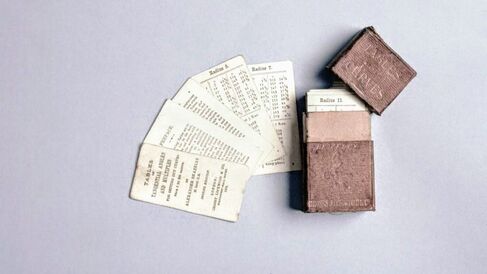

Pocket-sized reckoners had to present information selectively, and were often made for only very specific purposes, or to accompany some other instrument. Their small size made them more akin to handy tools than bound volumes. For example, when it became necessary to build railroads with tighter curves to save space, engineers had to carefully calculate curve radii so that trains would not derail. An engineer could consult these cards from 1878 by Alexander Beazeley(above), which were small enough to carry around in a pocket or lay on a theodolite while measuring angles.

Other reckoners were used to calculate interest over time, present exchange rates for mixed currencies, and set values on livestock and other agricultural goods. As markets fluctuated, they were updated. In the sciences, on the other hand, standard sets of tables played a crucial role in making experiments legitimate. Laboratories relied on sets of standard values, like the specific heat of a substance, for setting up an experiment as well as calculating results. In 1938, Ronald A. Fisher and Frank Yates published the first edition of Statistical tables for biological, agricultural and medical research, which helped to spread the application of statistical tests to the design of experiments and validity of results. It sold 22,000 copies by the 1960s, and became the most important statistical resource of its time.

Mikey McGovern

Mikey McGovern, 'Tables', Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge