Science in the Field

Astronomy in the British Empire was not just about star-watching from observatories and ships. In the colonies, astronomy was also an essential part of the ‘survey sciences’—a diverse range of geographical practices deployed to chart territory in the service of imperial settlement and administration.

This took astronomers out into the field as part of projects like the ‘Great Trigonometrical Survey of India’, a vast scientific and military undertaking to measure and map the entire Indian subcontinent.

Although we are currently closed to visitors, you can still enjoy the Whipple Museum from home in the following ways:

Search and browse through records and images of close to 7,000 objects, as well as records of our Trade Literature.

Enjoy a virtual tour of the Museum's 75th anniversary exhibition with the Curator of Modern Sciences, Dr Joshua Nall.

With your little ones, try a fun learning activity inspired by our collections.

Explore some of our collections in more detail here on our website, including in-depth articles and images that tell you more about a selection of our objects and subject areas.

Book an online learning session for your school class, uniformed organisation, or homeschoolers. Sessions typically last up to an hour and include practical activities to do at home or at school, looking at objects, and a chance to ask questions.

- Email our Learning Coordinator, Alison Giles to set up a session at are26@cam.ac.uk.

Read essays by renowned historians of science in our latest publication, Objects and Investigations. Each chapter focuses on a specific instrument or group of objects, ranging from an English medieval astrolabe to a curious collection of plaster chicken heads.

Watch presentations on some of our objects with unheard stories and enjoy visitors’ own creative interpretations.

Follow us on Twitter for daily tweets on fantastic objects, stories from our collections, and behind-the-scenes activities.

Buy homeware inspired by our John Stevens Henslow collection of botanical prints in the Curating Cambridge online shop.

We can’t wait to welcome you back in person, but in the meantime, stay safe and enjoy these resources!

While the museum is closed, we are developing online sessions for remote delivery to schools and other community groups. Please contact Learning Coordinator Alison Giles on are26@cam.ac.uk to arrange an online session for your group. All sessions are free of charge, although we encourage donations to the museum if possible.

Science through experiments

Key themes: Light and Shadows, Measuring, scientific skills.

Age range: KS2-3, small groups

Duration: 20-30 minutes per session, up to six sessions per unit

Format: Working with a box of equipment provided by the museum and online facilitation via video link, students work on different aspects of the science curriculum. They are encouraged to learn by doing and to hone the key scientific skills of questioning, observation, prediction and experimentation.

Object focus sessions

Key themes: Science; history; interpreting objects.

Find out more about an object from our handling collection in detail. Carry out a simple experiment related to it, explore an open-ended discussion question, and complete an imaginative activity.

Objects covered so far include the microscope, the telescope, computers and calculators, and a sundial, but we can find objects in our handling collection to fit most topics!

Age range: KS2, but can be adapted for KS1 or KS3 with objects chosen to fit specific topics. Families or small groups welcome.

Duration: 30-45 minutes.

Format: Led by the Museum’s Learning Coordinator via your preferred video conferencing platform. An adult must be present throughout the session.

Adult group talks: Objects from the Whipple Museum

Key themes: The museum itself; the history of science; scientific equipment.

Learn more about objects from our handling collection in this exploration of the history of the Museum and its displays through a wide range of scientific objects. There are over 100 objects in the handling collection so every talk is slightly different; if you have particular scientific interests that you’d like to cover then let us know in advance and we’ll see what we can do.

Age range: We’re too polite to ask, everyone is welcome!

Duration: 40 minutes plus time for questions.

Format: Talk by the Museum’s Learning Coordinator via your preferred video conferencing platform.

Talks for young people: Scientific Women

Key themes: The historical role of female scientists.

Find out about the lives and achievements of six female scientists from 1750 to the present day by taking part in activities related to their discoveries.

Age range: Designed for Brownies or Guides (with different activities for different age groups; Cubs and Scouts or other groups of young people are also welcome).

Duration: 40 minutes plus time for questions

Format: Talk by the Museum’s Learning Coordinator via your preferred video conferencing platform.

Cubs Astronomy badge session

Key themes: work through the syllabus of the Cub Scout Astronomy badge using objects from the Whipple Museum collections

Age range: Cubs

Duration: 40 minutes plus time for questions

Format: Talk by the Museum's Learning Coordinator with activities via your preferred video conferencing platform.

Held every February half-term, Twilight at the Museums is traditionally a time when our local museums open their doors to families for an evening of torch-lit exploration. Due to current COVID-19 restrictions, we might not be able to welcome you in person but we'll still be bringing you a taste of Twilight fun.

From Monday, 15 February the University of Cambridge Twilight at Home page will feature a whole load of twilight-themed activities, games and videos for you to enjoy. Whether it's getting outside and trying your hand at a bit of stargazing, or staying warm and having a go making shadow puppets, University of Cambridge Museums will have plenty for you to watch and do.

In this talk, we report on the co-production of a measure of thriving in collaboration with national poverty charity Turn2Us.

In opposition with the expert-driven approach common in the sciences today, in this project people with lived experience of financial hardship are involved in the development and validation of the indicators used to describe their lives.

A talk with Anna Alexandrova of the Department of History and Philosophy of Science.

Booking is essential -- Please book a slot on the Cambridge Festival Website.

An empire of science

This map shows the extraordinary scale of the ‘Great Trigonometrical Survey of India’, by far the largest and most complex land survey ever conducted in the British Empire.

The circles, crosses, and stars show the pendulum and astronomical stations that made up the Survey’s reference points. Each triangle is the calculated result of numerous angle and baseline measurements taken by teams of surveyors between 1802 and 1870.

The ‘survey sciences’ served in the front lines of the East India Company’s territorial conquest of India. Backed by British military power, surveyors worked for nearly a century to extend cartographic control—and with it administrative authority—across South Asia. As Clements Markham, Secretary of the Royal Geographical Society, haughtily declared in 1871:

“The story of the Great Trigonometrical Survey, when fitly told, will form one of the proudest pages in the history of English domination in the east.”(1)

Great theodolites

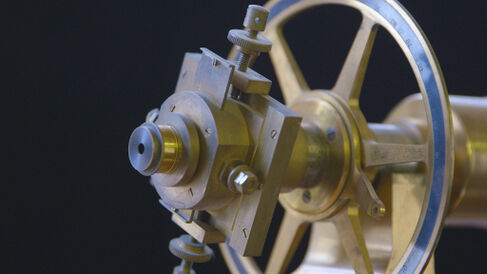

Theodolites like the example shown in Image 1 were an important tool for 18th- and 19th-century imperial land surveys, particularly for triangulation.

In this technique, the telescopic sight was used to accurately measure horizontal and vertical angles between distant vantage points; their relative locations could then be calculated using trigonometry.

Despite requiring at least two people to lift it, for serious survey work an instrument the size of the Whipple’s example would have been considered small. Increased accuracy in angular measurement is best achieved by making the circular measuring scales larger.

The ‘Great Theodolites’ used in the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India had a horizontal scale three feet in diameter and weighed over half a tonne, requiring a dozen strong men to carry them.

As the military surveyor J. A. Hodgson noted in 1822, this kind of instrument was only ‘portable’ because of the colonisers’ access to plentiful local manpower:

“In Instruments intended for India, solidity should be considered; we want those which will do their work effectually, and are not anxious that they should be small and easily portable, as we can always here find means of carrying them.”(2)

Read more: Survey instruments in India

Struggling in the field

Surveys and expeditions relied upon large quantities of instrumentation surviving transportation and use in often harsh environments.

George Everest, the sixth Surveyor General of India, wrote that instruments needed to be secured against “a puff of wind or a careless native,” and designed the rugged, compact theodolite shown in Image 2 with Indian survey work in mind.

Despite efforts to guard instruments against field conditions, surveyors’ own accounts are filled with complaints like that of Edward Garstin:

“I have one of the best levelling instruments in India … but owing to the negligence of my servants the stand is lost. … Although I have the theodolite which the liberality of Government formerly gave me to replace the instrument I brought from Europe and lost on service, yet it is so very bad an instrument that it is useless, as no possible adjustment can make it correct enough to ... place the smallest dependence on it.”(3)

Garstin and his fellow surveyors frequently described their equipment as fragile, erratic, and easily lost, or blamed local collaborators and servants for mishandling objects and hampering work. And they often highlighted their own particular skills at coaxing wayward instruments back into working order.

Such reports drew attention to surveyors’ triumph over adversity, and furnished excuses when data was deficient or incomplete.

References

1.Clements Markham, A Memoir on the Indian Surveys (London: 1871), p.124.

2.J. A. Hodgson, ‘Journal of a Survey to the Heads of the Rivers, Ganges and Jumna’, Asiatick Researches, Vol. 14 (1822), 60–152, on p.102.

3.Edward Garstin, letter to superiors at the Survey of India office, 13 Sep. 1820, as quoted in: R. H. Phillimore, Historical Records of the Survey of India, Vol. 3 (Dehra Dun: Survey of India, 1954), on p.212.

Joshua Nall

Joshua Nall, ‘Science in the Field’, Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge, 2020.