Parts of the Microscope

The proliferation of specialist slide rules in the eighteenth century inspired schoolmaster John Suxspeach to create a universal one. This was designed to be used in different disciplines and types of inquiry, and represents an early attempt to enforce universal standards through instrumentation.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, clockwork and precision engineering made it possible to build devices that could add and subtract at the turn of a dial. The designs of these adding machines differed in important ways. They both inspired more complex work, like that of Charles Babbage and Konrad Zuse, and made it possible to mass produce devices to aid in everyday arithmetic.

Entering the age of machines

The Enlightenment development of gear-driven mechanisms captured the popular imagination and inspired the design of amazing new machines. Devices known as 'automata', which often mimicked humans or animals, were invented by clockmakers to entertain the ruling classes and so win their favour. Amongst the most famous and advanced automata were a writing boy, various musicians, and a digesting duck capable of eating kernels of grain before metabolizing and defecating them.

A century earlier, John Napier had been restricted to paper or ivory to build calculating tools. But by the 17th century, the growing popularity of clocks and associated mechanisms meant that knowledge and working examples of gears, levers, cams, pulleys, and cranks were in wide circulation, offering exciting new possibilities for the automation of calculation.

All microscopes have a lens, mounted in a convenient way, usually with some method of holding a specimen or slide in place. Beyond this miminal description, microscopes can have focusing mechanisms, combinations of lenses, illumination devices, mirrors, and various other parts. This means that any two microscope designs can look very different.

Simple and compound 'microscopes'

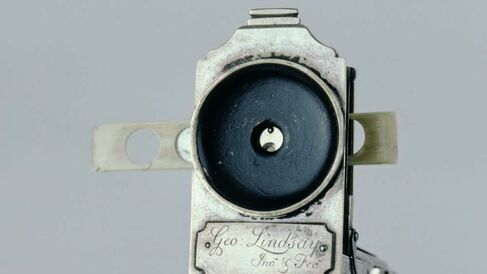

There are two main types of microscope. The simple microscope (Image 1) has only one lens, and the compound microscope (Image 2) has at least two. Single lenses have been used in various forms since antiquity. The compound microscope was invented at the end of the 16th century. The term 'microscope' always refers to an instrument made after the invention of the compound microscope; it was probably first used in its Latin form (microscopium) in 1614. The term originates from a combination of two Greek words: mikros=small and skopein=to look at.

Different designs

As the microscope became popular, more people with practical skills became involved in its use: 'microscopists' collaborated with instrument makers to create new designs, whilst some made their own instruments. One of the most famous early designs was that used by Robert Hooke. Hooke's microscope had a sturdy frame holding the body tube, which houses the lenses.

In the 18th century various designs were proposed, two of which are shown to the right. Image 1 is a pocket microscope. Pocket microscopes were popular because of their ingenuity and the fact that they could be used outdoors in the field. Image 2 shows a larger microscope, designed by John Cuff.Cuff's design looks more like our modern microscopes, and was very popular in the 18th century due to its stability and easy focusing mechanism.

Aside from microscopes that are intended for use outdoors in the field, most designs have a number of common features. These can be seen in the two images. Most microscopes have some kind of a stand, which holds the body tube, the lens(es), and sometimes a stage. The stage supports slides or specimens.

Focusing is one of the most important parts of microscopy. The distance between the lenses and the specimen, and between the lenses themselves, needs to be adjusted, and various focusing mechanisms have been used to do this. Another important task is the illumination of the specimen. If you were to look at a flea under a microscope in normal light it would be impossible to see anything at all. The flea would need to have a light shone onto it, or through it from underneath. Before the invention of electric lighting, candles, gas lamps, and sunlight were used. The light is usually shone directly into the body tube via a mirror; when the mirror is position beneath the stage, it is called a substage mirror.

Throughout the website and collections of the Whipple Museum you will see various microscope designs. However, they all have common features, and most work in the same way.