Maps of the Heavens

Many early-modern astronomical instruments - including sundials, quadrants, and astrolabes - carry maps of the heavens. An important method for drawing such star maps is called stereographic projection, the plotting of 3 dimensions onto 2 dimensions. Such projections allow complex astronomical calculations to be made without the use of a cumbersome celestial globe or advanced knowledge of mathematics.

The graphic telescope is an optical aid for artists. It was patented in 1811, and is a device which enables artists to view magnified images and trace them onto paper.

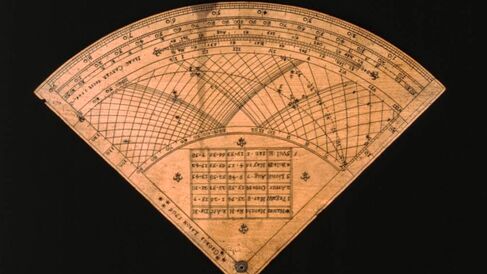

The quadrant is an instrument used to simplify astronomical calculations and to make observations. It also carries an image of the heavens, and can be understood as a means of gaining practical knowledge of geometry and astronomy. The Whipple has 14 such instruments, one typical example of which is this boxwood 'Gunter-type' quadrant, made by Isaac Carver in 1706.

Stereographic projections provide striking images: the heavens are displayed in two dimensions and constellations can be elaborately drawn. The engraved lines are impressive examples of the skill of instrument makers. But what can these images of stereographic projection tell us about how instruments were used?

Classical sources

The principles of stereographic projection (Image 1) were known in antiquity to the Greek astronomer Ptolemy (circa 100-circa 170). These principles were transmitted to early modern scholars, largely through Arabic writers. One major source in the 17th century was Francois de Aguilon'sOpticorum (1613) concludes with a long account of stereographic projection. Image 2 is taken from this account and shows a literal projection of the heavens, with a light being shone through an armillary held by Atlas. The engravings were made after original drawings by Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640).

Another important type of projection found its first description in the Roman author, Vitruvius, (1st century BC) whose De Architectura featured a section on the analemma (Image 3). The analemma is a diagram that can be drawn with no knowledge of projections or the related mathematics. Despite its simplicity the analemma actually depicts lines representing the great circles of the celestial sphere, as if they are projected through the globe from one side. This diagram and instruments based on it were popular in the early-modern period, and were used to solve navigational, astronomical, horological, and geometrical problems.

Theory and practice

As well as the practical benefits of using projections, their construction and use was taught in various books, in the curricula of schools and in private tuition. Projection was taught because it neatly combined learning about the celestial sphere and practical geometry. The title of a book by Thomas Stirrup, published in 1652, reads: Horometria: or The compleat diallist ... With the working of such propositions of the sphere, as are most usefull in astronomy and navigation both Geometrically and Instrumentally.

Boris Jardine

Boris Jardine, 'Maps of the heavens on astronomical instruments', Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge, 2008