Slide Rules

The predominant calculating aid for nearly three centuries, the slide rule came together gradually as mathematicians used Napier's logarithms in their instruments. Slide rules came in many shapes and sizes, with different rulings suited to their specific application.

One of the central themes of the history of the microscope is the history of lens development. Until 1830 two problems hindered lens manufacture: spherical aberration and chromatic aberration. Around 1830, in collaboration with Joseph Jackson Lister, William Tulley made one of the first microscopes that corrected for both chromatic and spherical aberration.

The Whipple Museum has five items made by the Italian professor Giovanni Battista Amici. Working in the early- to mid-19th century, Amici's microscopes were owned by some leading members of the scientific community. One of the Whipple's examples was supposedly Amici's own working microscope; another belonged to an Irish astronomer, Thomas Romney Robinson.

John Stevens Henslow and his son George were both botanists, and both studied at the University of Cambridge in the 19th century. The Whipple Museum has over 100 botanical teaching diagrams illustrated by the two men. In addition, the Museum has one microscope bought by John Stevens Henslow, and a microscope and micro-spectroscope given to the University by George Henslow.

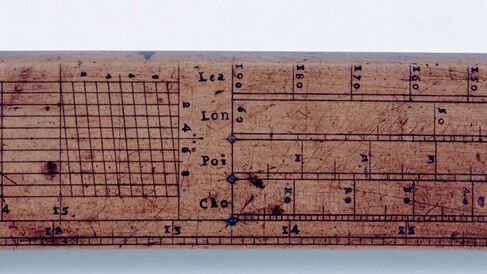

Gunter's line

The slide rule's origins can be traced to the British mathematician Edmund Gunter (1581-1626). Gunter distinguished himself through the design of calculating devices, and was the first to use logarithmic scales for physical instruments.

He arranged logarithms into a scale, known as Gunter's line, which was then made into a two-foot rule with one side marked with logarithms and the other rulings for navigation (above) . By using a logarithmic scale to enable the conversion of multiplication and division into addition and subtraction, these rules were the predecessor of the slide rule. The example shown here was made by Robert Yeff in 1712, and was probably used as a general-purpose calculator at sea, where it would have been referred to simply as a "Gunter."

Read more: logarithms and their uses

Read more: the Gunter quadrant

"The true way of Art"

The slide rule proper is believed to have been invented in the 1620s, when the Reverend William Oughtred (1574-1660) in Surrey put together two Gunter scales and slid them alongside one another. This way, he could calculate without the use of dividers, which were required to operate both the Gunter's scale and the sector.

Oughtred then designed a similar apparatus using scales on concentric circles in order to make the device more compact (Image 2). The instrument in the Whipple Museum's collection is one of the first produced by Oughtred's instrument maker, Elias Allen, in about 1635.

Whereas Napier had enthusiastically applied his talents to devise a number of aids for calculation, Oughtred apparently despised instrumentation for its own sake, and kept his methods private. He published a Latin treatise in 1631 only to mitigate a priority dispute with a former student over the device.

He eventually permitted another student to translate the work into the English vernacular, but not without a cautionary message:

"That the true way of Art is not by Instruments, but by Demonstration: and that it is a preposterous course of Artists, to make their Schollers only doers of tricks, as it were Juglers" (1)

Changing shapes and sizes

The linear slide rule most recognised today gained popularity in the latter part of the 17th century.

It used a sliding piece of wood in a larger 'stock' with rulings on both pieces, with a cursor to align numbers.

For the first century of their existence, slide rules were typically crude and inaccurate, owing to the poor scale-dividing technology available. But as time went on, they became advanced and powerful tools for calculation.

The cylindrical slide rule shown here (Image 3) was developed in the late 19th century by E. Thacher, and had a scale that was 40 times greater than a standard linear rule, in addition to a magnifying glass for improved accuracy.

Thacher's model was just one of numerous new slide rule designs developed during the instrument's lifetime. Many were developed for use in specific tasks, such as calculations relating to brewing or the measurement of radiation doses.

Other designs purported to be 'universal' instruments, capable of solving numerous different types of numerical problem.

References

- W. Oughtred, The Circles of Proportion translated by W. Forster (London: 1632), available online.

Mikey McGovern

Mikey McGovern, 'Slide rules', Explore Whipple Collections, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, University of Cambridge.